by Scott Smith

What’s not to love about turtles? They are among the world’s most cherished species and always a sight to behold,whether it’s a giant Galapagos tortoise numbering across a desert isle, a glistening loggerhead turtle trundling ashore to bury her eggs in the sand or simply a red-eared slider sunning itself on the bank of a local pond.

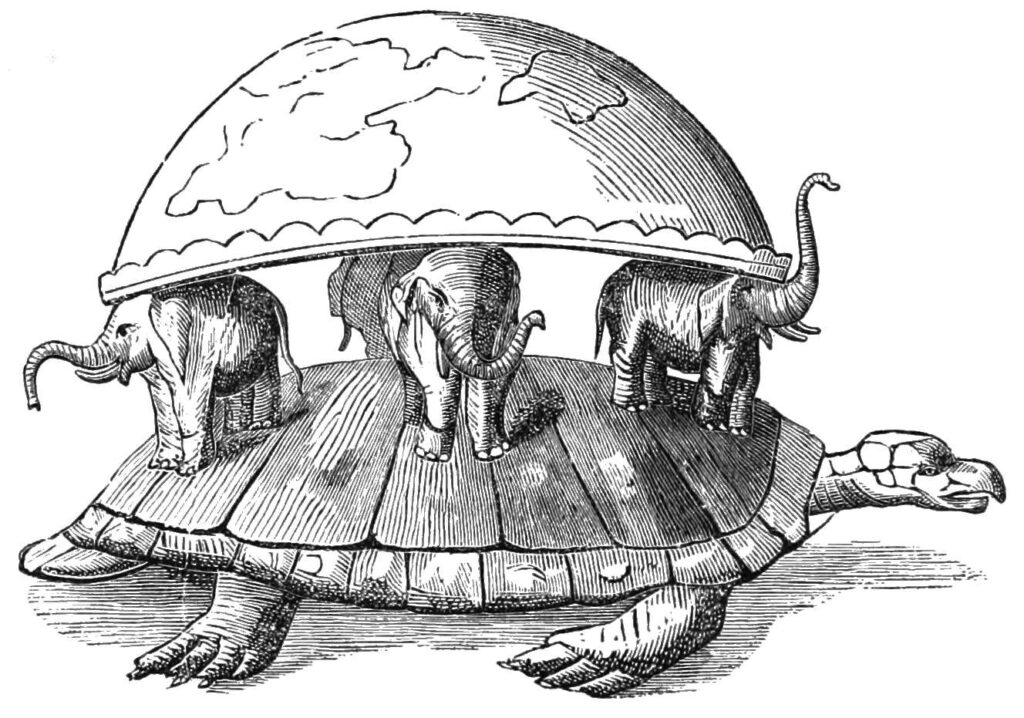

Turtles have always held a special place in the human heart. Who doesn’t cheer on the dogged tortoise in its race against the arrogant hare? In Hindu Mythology, the World Turtle supports four elephants on its back, which in turn carry the weight of the entire planet. For Native Americans, earth was created by dirt piled atop a turtle’s shell; earthquakes happened when the turtle grew tired of its burden and gave the world a shake.

Now the heavy load has shifted back to humans, for turtles the world over are in dire need of our help. Among vertebrate orders, turtles and tortoises are second only to primates in the percentage of threatened species; 60% of the 360 modern species are considered threatened or already extinct. Poaching—driven by a growing demand for pets in the U.S., Asia and Europe—is contributing to the global decline of rare freshwater turtle and tortoise species. Other wild species are captured and sold to collectors or taken for commercial breeding, food, decorative products and traditional medicine. And to be sure, this ancient species faces the same modern threats as other wildlife—from habitat destruction and climate change to road mortality and invasive new predators eating their eggs.

Since 2018, the Collaborative to Combat the Illegal Trade in Turtles—an organization of state,federal and tribal biologists who combat poaching of North American turtles—has documented at least 30 major smuggling cases in 15 states. Some involved a few dozen turtles, others several thousand. To cite just one example: In early 2022, a man in North Carolina was sentenced to 18 months in prison and fined $25,000 for trafficking turtles in violation of the Lacey Act, which bans trafficking in fish, wildlife or plants that are illegally taken. The man sold 722 Eastern box turtles, 122 spotted turtles and three wood turtles for more than$120,000. The illegal haul had a value of $1.5 million in Asia, reported the New York Post.

“Illegal trade is huge, and no one realizes it happens in their own backyards,” said Jenny Dickson, director of the Wildlife Division at Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. Of the state’s eight native land, freshwater and coastal turtle species, Dickson cites the Eastern box turtle as “one of the most rapidly declining turtle species in the region,” largely due to illegal collection for the pet trade.

Turning a rib into a shell

Time for a bit of turtle biology. Part of the order of animals known as Testudines, turtles and tortoises predate the age of dinosaurs. Not all turtles are tortoises, but all tortoises are turtles.

The biggest difference is that turtles spend most of their time in the ocean or near water while tortoises live exclusively on land. (What about terrapins, you ask? The name is mostly used to describe turtles that live in freshwater.)

Whether they spend their lives roaming the seas or reside on hard ground or boggy marsh, most turtle species lay eggs on land and bury them in nests, usually unguarded. Tortoises typically have more rounded,dome-shaped shells and consume a vegetarian diet, though some won’t pass up an insect if they can catch it. While commonly found in hot, arid climates, tortoises live across much of the world; some even hibernate in their cold native climes.

With paddle-shaped front legs and webbed back feet, turtles are well-equipped to call lakes, rivers, wetlands and ocean waters home. Their shells are thinner and more streamlined for navigating aquatic environments. Turtles eat both plants and animals,including algae, sea grass, jellies, small fish and crustaceans. Marine turtles also have tear glands that help them rid their bodies of excess salt. One,the leatherback, rules as the biggest turtle, and can weigh 2,000 pounds and reach over six feet in length. The Galapagos tortoise tops out at about 1,000 pounds and four feet long but takes the prize for longevity; they live for 100 years or more in the wild.

While a lack of predators, particularly in isolated environment like the Galapagos Islands, can allow for gigantism, the species can also go small: The speckled tortoise, native to the deserts of southern Africa, is only three inches in length, about the sizeof the bog turtle, which calls North America home. Both are considered endangered.

And about that shell: A turtle’s carapace develops from ribs that grow sideways and turn into broad flat plates that join to cover the body. Its outer surface is covered in scales made of keratin, the same material of hair, horns and claws. Another thing all these shelled creatures have in common is that they are slow to reproduce, have high egg mortality and are often fairly easy to catch. And therein lies the problem.

Combatting the international pet trade

North America’s imperiled turtles got some much-needed attention at the most recent Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which was held in Panama In November. Members from 160 countries considered protections for 21 turtle species hunted in the U.S. for their meat or for the exotic pet trade.

Though enforcement of these protections is often lacking, tougher regulations regarding the global trade in the species—among them two types of snapping turtles, three species of softshell turtles and five kinds of broad-headed map turtles—is a “critical step” to ending “loopholes that have enabled unsustainable collection for international trade,” said Martha Williams, director of the U.S.Fish and Wildlife Service.

Friends of Animals Wildlife Law Program has been fighting for the survival of turtles around the world for decades. In 2014, FoA joined other wildlife groups in petitioning the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to recognize the serious threats to spider tortoises and flat-tailed tortoises, native to Madagascar, and move the species closer to listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Both species are mainly threatened by the international pet trade. ESA protections would help eliminate the part played by the United States in the illegal trade in these tortoises. Listing species outside the U.S. can both protect the species domestically by preventing illegal imports and help focus U.S. resources toward enforcement of international regulation and recovery of the species. FoA is still waiting on a final findings as to whether FWS will list them under the ESA.

More recently, FoA went to bat for the Egyptian tortoise. Urban sprawl, tourist development, agricultural expansion and cattle and sheep grazing have already destroyed nearly 90 percent of the tortoise’s historic range. It’s believed to be extinct within Egypt but can still be found in Libya and in parts of the Negev Desert in Israel. Despite an Appendix I “threatened with extinction” listing by CITES, there has been consistent illegal trade in protected tortoises, and wild-caught individuals are exported under the guise of being bred in captivity.

In 2015, Friends of Animals received a positive 90-day finding on its petition to list the Egyptian tortoise under the ESA. In early 2022, FWS proposed to list the Egyptian tortoise as threatened. FoA is hopeful that the protections be finalized in early 2023. The wheels of justice often turn as slowly as those of a desert tortoise. But the more people know about the plight of turtle populations the more effective we can all be in saving this ancient and honored species.

Take action for turtles: We’ve got your back.

If you’re out hiking and come across a turtle in its native habitat, consider yourself lucky—and leave the turtle alone. In most states, it is illegal to keep native turtle species as pets.

It also is illegal to remove turtles from the wild, though some states, including Connecticut, allow the capture of some types of turtles, including the snapping turtle, for personal consumption.

If you find a turtle in the road, pull over and park safely. If traffic permits,help them cross in the direction that they were going. Be careful about handling any turtle, especially one with a long tail. It’s likely to be a snapping turtle and can bite. A big turtle’s claws can also cause injury. If a shovel’s handy, use it gently; otherwise be patient as the turtle finds safety on its own.

If you find an injured turtle, call your local animal control officer, veterinarian or humane society for help locating a certified wildlife rehabilitator who is qualified to provide care.

How to spot turtle poachers–and what to do about it

Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation (PARC), a nationwide network, provides this advice about what to do if you suspect someone is illegally collecting or selling wild turtles. Here’s what to lookout for:

● People with bags, poking around in wetlands and along streams, or flipping over logs and rocks

● Cars parked near forested areas with collection equipment (like nets and containers) visible inside

● Sheets of metal or plywood that have been laid on the ground to attract cold-blooded reptiles and amphibians

● Unmarked traps set in wetlands. Traps for research will be clearly marked

● Unattended backpacks or bags left in the woods,along a trail or near roads. Don’t ever open a suspicious bag or container—report it to authorities. Note the exact location, what happened, and who was involved (persons, vehicles, and other witnesses). If it is safe to do so, take photographs that can corroborate your report—for example, the license plate of a vehicle or serial number on a turtle trap.

● Do NOT confront suspicious persons or try to stop a crime yourself. Prioritize your safety, and then contact the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service by phone (1–844-FWS-TIPS) or email (fws_tips@fws.gov), or contact your state wildlife agency

This article was originally published in the Spring 2023 edition of Action Line magazine. View the full magazine here.