Scientists are finding answers in the wild, not in entertainment parks

By Nicole Rivard

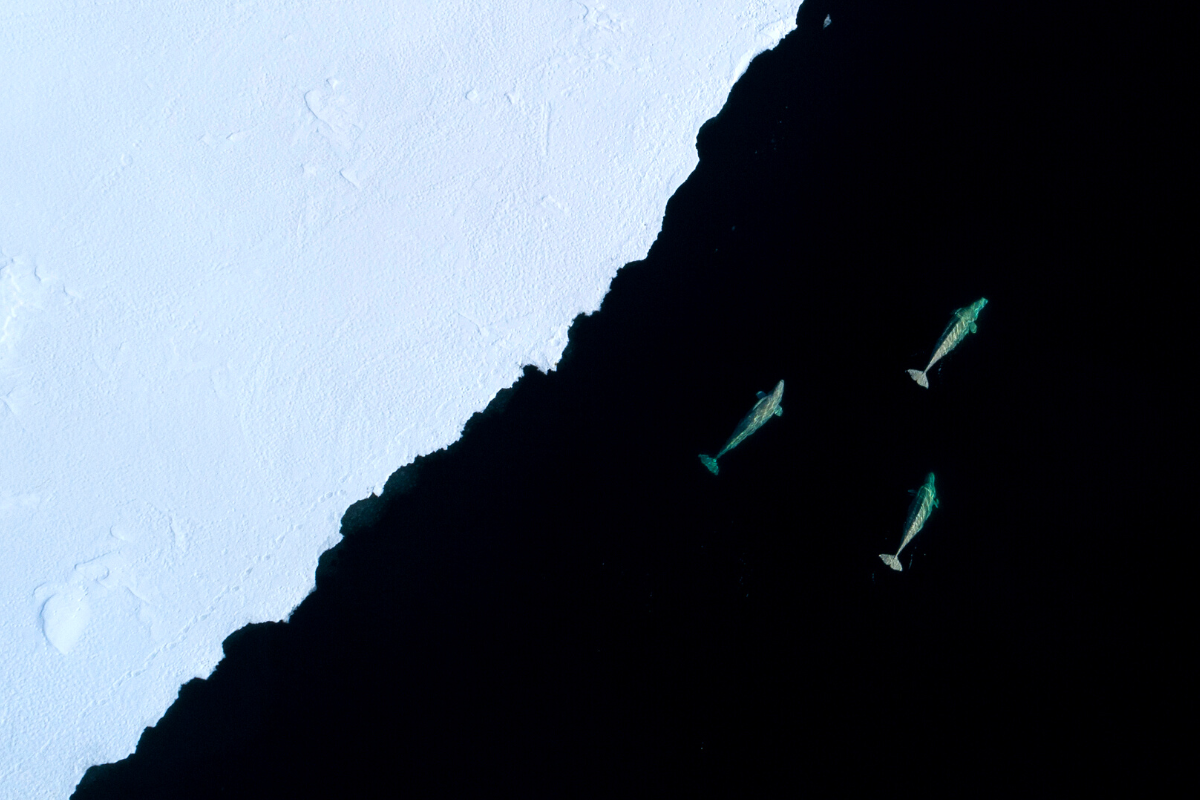

Beluga whales are often referred to as canaries of the sea because of the whistles, squeals, moos, chirps and clicks they use to communicate, navigate and hunt for prey.

Now, thanks to new observations in the wild, they are also becoming known as the social butterflies of the ocean. Not only do they regularly interact with close kin, they also frequently associate and form long-term affiliations with more distantly related and unrelated individuals.

“This new understanding of why individuals may form social groups, even with non-relatives, will hopefully promote new research on what constitutes species resilience and how species like the beluga whale can respond to emerging threats including climate change,” said Greg O’Corry-Crowe, research professor at Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanic Institute.

Another groundbreaking study of belugas in the wild is also making waves—beluga whales appear to value culture as well as their ancestral roots and family.

“What intrigued us most was whether particular whales returned to where they were born or grew up, and if this was an inherited behavior,” O’Corry-Crowe said. “The only way that we could definitively answer these questions was to find and track close relatives from one year to the next and one decade to the next.”

O’Corry-Crowe and his team concluded that from one generation to the next, the whales have been passing along the knowledge of their travels and their routes. He focused on the migratory patterns of beluga whales in the Gulf of Alaska, the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort Seas, and the Sea of Okhotsk over three decades.

Yes, other animals migrate on an annual basis using environmental cues such as day/night, chemicals, magnetism, etc.

“But what makes the beluga migrations especially interesting is that they’re based on social learning from mothers to children. And that’s the basis of culture,” said Lori Marino, neuroscientist and founder of the Whale Sanctuary Project. “Belugas aren’t just a migratory species; they’re a migratory culture. And I think that is what would surprise people the most about them.

“And that their friendships go well beyond who their family members are. They have a very complex social landscape they navigate through. There is no way to have that social stimulation in a tank at an entertainment park,” Marino added.

Friends of Animals couldn’t agree more. That’s why during the 2023 legislation session we plan to work on getting a bill reintroduced and passed in Connecticut that would ban the trade and sales of cetaceans in our state and ban cetacean breeding in captivity.

Mystic lying, whales dying

Unfortunately, it’s too late for the two belugas—Havana and Havok, who recently died at Connecticut’s Mystic Aquarium. Another remains in intensive care. The three were transported in the dead of night with two others in May 2021 from Marineland in Canada despite countless warnings that the move would risk their lives.

Friends of Animals contested the transfer in a court battle in 2020.

Adding insult to injury, more than 200 online bidders and attendees of a live auction last summer raised $3.4 million for Mystic Aquarium. One of the hot-ticket items—naming rights for three of the belugas; the right to name the fourth came from a raffle.

A scathing USDA report made public in April 2022 revealed five-year old beluga whale Havok’s last eight hours before he died on Aug. 6, 2021 were full of extreme discomfort and distress. However, no one told an attending veterinarian until after he died.

Later that August, after another beluga had fallen seriously ill, staff from the CT Examiner interviewed Stephen Coan, Mystic’s CEO, who continued to defend the appropriateness of moving the belugas from Marineland for “vital research that will help critically endangered beluga populations in the wild and preserve the species.”

When asked if there is a scientific rationale for studying marine mammals in captivity rather than in their natural environment, Coan replied: “You can’t study belugas or other whales in the wild in any substantive way. The technology doesn’t exist, and it is simply not practical to do so.”

“That is a completely false statement,” Marino said, adding that Coan’s comment is dismissive of field researchers like O’Corry-Crowe, Hal Whitehead, Luke Rendell and Valeria Vergara.

“Essentially, everything we know about social and communicative complexity of belugas and other whales comes from field studies. None of these things can be studied in concrete tanks,” Marino said.

Information gleaned from the wild about beluga whales’ social learning, kinship and traditional use of areas is key to preserving the species. A simple Google search underscores this and provides more evidence that Coan is lying.

For example, the first long-term acoustic monitoring effort across Alaska’s Cook Inlet provides the most comprehensive description of beluga whale seasonal distribution and feeding behavior to date, which is critical for understanding and managing potential threats impeding recovery of this endangered population. Cook Inlet belugas were listed as endangered in 2008.

In addition, researchers can now determine the age and sex of living beluga whales in Cook Inlet thanks to a new DNA-based technique that uses information from tiny samples of skin tissue obtained with a small biopsy dart. Accurate age estimates are vital to conservation efforts for Cook Inlet belugas. Previously, researchers could only determine the age of beluga whales by studying the teeth of dead animals.

This new technique is helping a lab in San Diego study pregnancy rates in Cook Inlet belugas using hormones found in their blubber. “As soon as we got the ages and plotted pregnancy or not versus age, we noticed that it was only the older whales in our study that showed a fairly high pregnancy rate,” Paul Wade, a scientist at Alaska Fisheries Science Center, told Alaska Public Media.

When those findings are compared with that of healthy beluga populations, they show reproduction among Cook Inlet belugas could be delayed, which might be a sign the population is struggling due to external factors, like a lack of food, according to Wade.

No matter what Mystic claims, it is this type of field work that is bringing biologists closer to knowing why Cook Inlet belugas aren’t rebounding and how to save them.

When I visited Mystic Aquarium in the summer of 2020, I hoped there would be some educational aspect to motivate visitors to protect belugas and their ocean habitat. However, staff members only provided a canned speech about Kela, Natasha and Juno’s age, weight, birthplace, that they don’t have dorsal fins and that they have a blubber for insulation.

As I made my way to the underwater viewing area, a crowd had gathered, waiting to take a selfie with the belugas. As families posed, I thought to myself—shame on Mystic. All an entertainment park does is strip wild animals of their dignity.

A photo op is not research, education or conservation, unless you are researching how to make more money.