By Janis Carter

I sleep on a slab of cement raised about a foot high from the floor of my cage. A slim foam mattress is propped on top. The mattress is thick enough to have a roadway of tunnels eaten through by rats in search of safe accommodation from snakes.

On the side of the cement slab, I once carved the names of all the non-human creatures who had shared my bed. Morris, a warthog, is among the names listed. His collar, a thick leather belt painted with white luminescent paint and topped with a scattering of macho silver studs, hung over my bed for decades. I recently took it down for safekeeping and it now sits in a box of treasured objects along with Lucy the chimpanzee’s mirror.

Although our work at the Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Project in the River Gambia National Park in Africa focuses primarily on the care and welfare of chimpanzees, we often receive or confiscate other wild individuals who have been captured and/or need our help. Many years ago, while out hunting with their dogs, two young boys—cousins and both named Lamin—discovered the nest of a warthog. Three young piglets were huddled together in a tight bundle in the ground-hole of a large baobab tree. Taking advantage of the absence of the mother warthog, the boys removed her babies.

A born survivor

It was serendipitous that two days later, our staff happened to pay a visit to the family of the young hunters. There they learned of the warthog capture and the death of two of the piglets. Barely able to stand, the tiny survivor was tied to a chair with a rope attached to his waist. His foreleg had an oozing sore where the rope had been previously tied too tight, cutting through the flesh and tendon of his spindly little leg.

His wound was already infected, and he looked weak and dehydrated. The odds were clearly not in his favor. Holding out for a miracle, I decided to give the sad little fellow a name—I called him Morris.

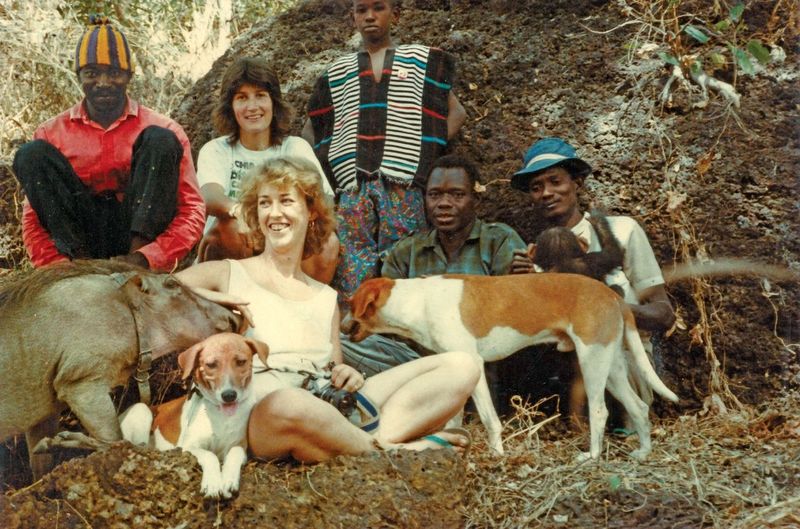

As I was traveling back and forth to Guinea, it made perfect sense that Gillian, our Scottish volunteer at the time, would take over as the primary caretaker for Morris. Initially, Morris was reluctant to feed from a syringe, but once he started to drink, he never stopped. After a couple of days, he graduated to baby bottles and from there to oatmeal. Within a short period of time, Morris joined in for mealtime with our three camp dogs: Spinner-spin-spin, Buckie and Broncho.

Morris had a voracious appetite, and his favorite meal was groundnut sauce with rice. Once he devoured his own meal, he would hover over the others’ snorting and grunting while they hastily tried to finish their own food. Using his big head, which looked disproportionately large in comparison with his body at that age, he pushed his way in, clearing their plates of any remaining crumbs.

In no time at all Morris was a full-fledged member of our dog pack, playing with them throughout the day and curling up for naps during the hot afternoon. But there was one characteristic of Morris that differed from his dog companions. Morris had a sweet tooth.

The cookie thief

I had recently moved off one of the islands in River Gambia National Park where I had been living in a tent for several years while rehabilitating a group of chimpanzees. A cage was constructed around the tent to protect my possessions from the curious chimpanzees who were serious object manipulators. When I moved off the island, I brought the tent and cage with me. Initially I set up only the tent, roughly 100 meters from the rest of the camp. I traveled by boat from camp to the island to see the chimps every afternoon.

I almost always had a package of cookies stashed away in my tent, hidden in a plastic bag so they would not attract ants. On my return from the island one afternoon, before even reaching the door of my tent, I could hear Morris’s grunts. Looking inside, I was appalled to see my meager possessions strewn from one side to the other along with an empty wrapper from a packet of cookies. Caught red-handed, with cookie crumbs on the tent floor directly in line with his big snout, Morris knew he was in trouble.

But he also knew exactly how to wiggle out of his dilemma. I called it his circus act—looking straight at me he fluttered his long, silky black eyelashes. Tilting his head back just a bit, he rolled his beady little eyes as if he was getting dizzy. Finally, while standing in place, he spun rapidly around in very tight circles before plunging out the mosquito net window of my tent.

Having survived nearly seven years on the island with a family of chimpanzees, my tent was destroyed in a matter of weeks by Morris and his propensity for cookies. For a variety of reasons, Morris being one of the foremost, I decided to reinstall my cage.

A motley crew

When the dogs set off to visit their dog friends in the village, Morris always joined them. It was an amusing sight to see the four of them trotting off down the narrow forest path in a straight line. Broncho was always in the lead and Morris always brought up the rear. He had a spring to his gait, bouncing off his tiptoes with his tail standing straight up like an antenna topped with a small tuft of hair. On one of these visits Morris discovered a groundnut farm that had recently been harvested with a pile of groundnuts ready for transport. He was busily chomping away when the farmer saw him and chased him away. We received similar reports over the following days until the chief of one of the villages sent us a message that we needed to keep Morris tied up.

Concerned with Morris’ welfare, we took the warning seriously. We were aware that the fact that no one ever shot Morris was a tribute to the relationship we had with the villagers and the extent of their tolerance. But we also knew that there were limits to their patience. We bought Morris a collar and painted it with white luminescent paint to help farmers and villagers distinguish him from wild warthogs. We also painted his name across his big backside. We knew this was not enough to stop him from leaving camp, so we hired a full-time babysitter named Satala. Sometimes, in the heat of the afternoon, Satala fell asleep. And when he did, Morris took off.

The great escape

On one of his escapes, Morris ran into a group of young boys and men engaged in the rituals of male initiation. During this symbolic passage from youth to manhood, young boys between the ages of roughly 8-13 spent several weeks in the forest during which time they were circumcised and taught survival skills. Their meals were often brought to them by men from the village who visited with the boys, providing words of wisdom or instruction. On this occasion a man from Guinea Bissau as with the boys. He was a Manjaco, a non-Muslim ethnic group that eats pork.

Morris’s sudden appearance at the sacred gathering could not have been more ironic. Sporting his newly emerging tusks, which signified his own passage to manhood, Morris stood robust and regal. Among the group of youths facing him, were his two young captors.

If ever there was a perfect example of karma, this was it. An uncertain silence set in, and no one moved. The spell was broken when the man from Bissau grabbed his cutlass and set out to kill Morris.

Sensing danger, Morris took off. The man followed swinging his cutlass in the air while screaming to the others to help him in his pursuit. The other adults joined the chase, but not to kill Morris. They were screaming at the man to stop because they all knew this was no run-of-the-mill warthog; this was Morris. Fortunately, Morris arrived home that afternoon, unscathed but exhausted. It was a close call for Morris but one that made us think seriously about his future.

We were all immensely proud of Morris when his tusks emerged completely. He was already huge and could knock people over if he wanted. Though he maintained a maternal feeling for Gill, his feelings for me bordered on being amorous. There was roughly 100 meters of forest between my cage and the camp. Hidden in the bushes along the path, Morris would often jump me as I walked between camps. If he succeeded in knocking me down, he would try to mount me. At roughly the same time Morris became very protective of the camp and those of us who lived there. People from the village who wanted to visit us would yell from the top of the cliff for us to come and escort them safely into the camp. We knew we needed to distance Morris from people for his own safety as well as theirs. As the island had warthogs this seemed an ideal solution.

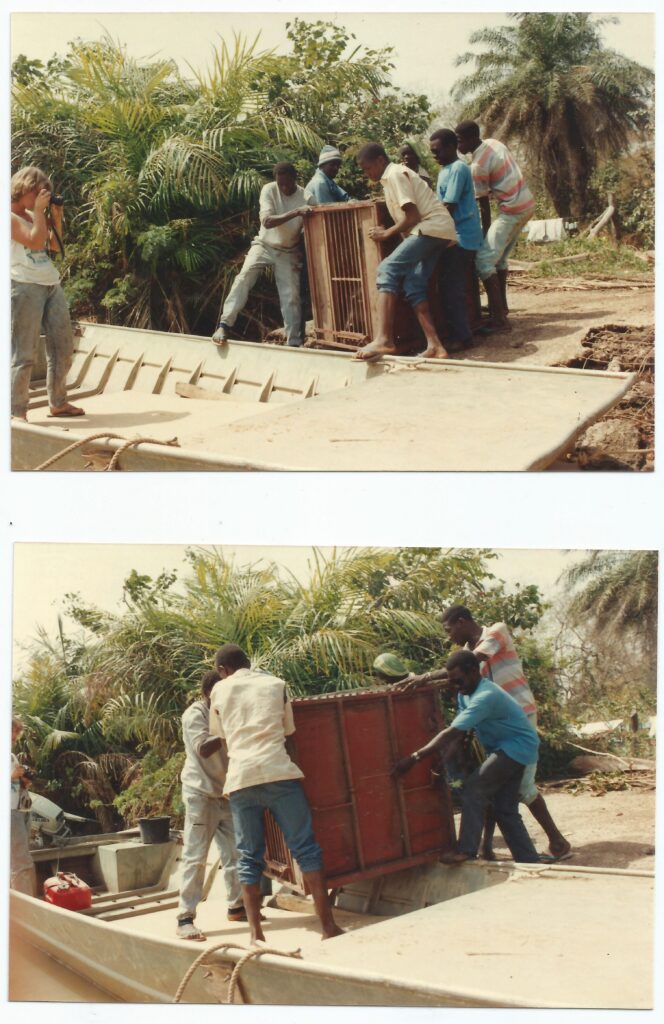

Morris was still reasonably manageable, so it was not too difficult to get him to go into one of the steel transport cages for large chimps. We loaded the cage on a flat boat which could get close to the island. By opening the cage door Morris could simply walk out of the cage directly onto the land. We released him on the southern end of the largest island, near my old camp, in a swampy area that warthogs frequented. Although saying goodbye to Morris was emotional for all of us, we knew he was not far and would still be under our protection in the national park. We were all speechless when two days later, Morris had returned to camp tired and hungry but happy to finally be home.

A new path

Becoming a bit desperate, I contacted the Senegal Department of National Parks and asked for permission to release Morris in the Niokolo Koba National Park, an expansive savannah park almost as large as the country of The Gambia. I felt certain that Morris would be safe there. After much discussion our permission was granted.

The plan was for Gill and Rene to take Morris in a pickup in the same transport cage we used to ferry him to the island. They would travel at night when it was cooler and hopefully arrive early morning in time to release him by sunrise. We said our final goodbyes to Morris at dusk and they left soon after.

Despite meticulous planning and acquiring all the necessary documents, there were a few administrative hiccups at the border posts between The Gambia and Senegal and even more when they arrived at the entrance to the park. As the delays increased, so did the tension for Gill and Rene. They knew Morris could not stay in the cage during the stifling heat of midday and early afternoon. They finally received the okay and Morris was released.

Exhausted from the journey and overheated, he lay down in the shade next to the pickup. Rene, who was alone with him at this point, grew concerned that the trip combined with the heat may have been too much for Morris. After some time, Morris stood up. He greeted Rene and drank some water before setting out to explore.

He took the lead, wandering down the path away from the vehicle. Rene followed. Eventually Morris stopped looking back for Rene and gradually, at his own pace, he sauntered off in search of his new path in life.

Life at camp was never the same without Morris. His strong and forceful character made him impossible to ignore when he was with us, and his absence painful to bear. Morris was a born entertainer and he loved to make us laugh.

Beyond a shadow of a doubt, he had the most superb sense of humor of anyone we ever raised and would raise in subsequent years. He remained gentle and affectionate with those of us he loved. And even when he was mature, I don’t think a day passed without him snuggling up to Gill for a few hugs.

Though Morris was with us for a relatively short time, he left behind a treasure chest of stories that we continue to share among ourselves and others…even almost 40 years later. That we had the pleasure of sharing those experiences with him was a gift to all of us who knew him.

Janis Carter, who was recognized by Smithsonian Magazine as one of “35 who made a difference,” is director of the Chimpanzee Rehabilitation Project, which was established in 1979. In a November 2008 landmark agreement with the Gambian government, Friends of Animals agreed to help fund the project. It is home to approximately 140 chimpanzees who live in four groups in relative freedom—without bars or cages—on three of the park’s five islands. For information on visiting the CRP, send an email to baboonislands@gmail.com.