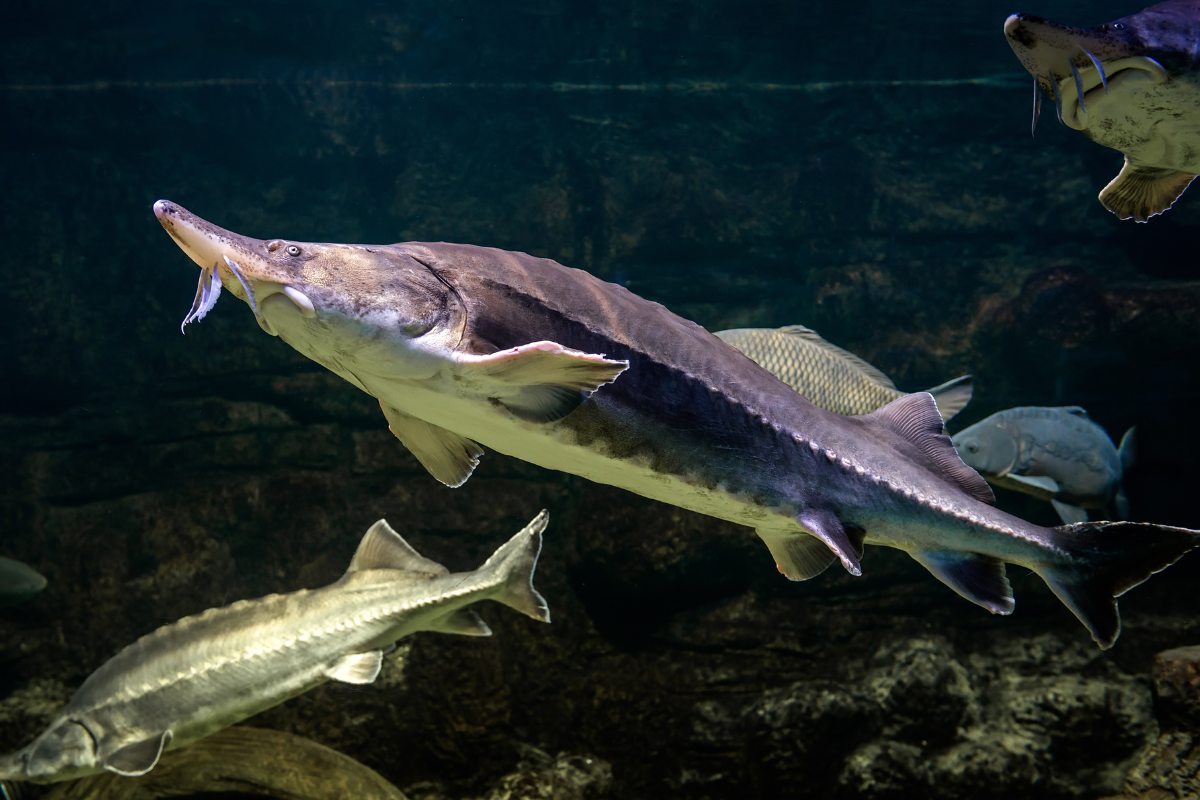

Russian sturgeon and three other species of the large caviar-producing fish found around the tumultuous Black and Caspian sea regions could get Endangered Species Act protections under a Fish and Wildlife Service proposal filed May 25.

FWS proposed listing the Russian, Persian, ship and stellate sturgeons under the ESA

The proposal was a longtime coming—it is in response to a March 2012 petition to list 15 sturgeon species by Friends of Animals and WildEarth Guardians. Sturgeon are described as the most imperiled group of animals on earth.

“This is great news and long overdue,” said Jennifer Best, director of Friends of Animals Wildlife Law Program. “We are pleased that Friends of Animals continues to help tear down the barrier that for too long has prevented sturgeon from receiving the ESA protections they need and deserve.”

FoA’s earlier victory came in 2014, when the first five species of sturgeon were listed as endangered because of severe threats posed by human exploitation, dams and pollution. The five species included the Sahhalin, Adriatic, Chinese, Baltic and Kaluga sturgeons.

The four new subspecies proposed for protections are referred to together as the Ponto-Caspian sturgeon. They prowl the rivers of the Black, Caspian, Azov and Aral sea basins, where they are hunted not so much for their meat as for caviar.

FWS routinely lists species endemic to other countries to restrict commercial use of products related to killing that animal. In this case, it will allow fish and wildlife officials to restrict the import of caviar derived from the four subspecies of sturgeon. The listing also helps raise awareness about the plight of these animals in other countries.

While human consumption of caviar is a factor in the decline of the species, dams on the Danube River and the Volga River, Europe’s two largest rivers that feed the Black and Caspian Sea, encroach upon the fish’s habitat.

“Nearly 100 dams at least 26 ft tall are present in the Caspian and Aral Sea Basins, and approximately 300 such dams dot the Black and Azov Sea basins,” the Fish and Wildlife Service said. “These dams are effectively impassable for sturgeon, eliminating the fishes’ ability to migrate to and from spawning grounds upstream of such barriers.”

There is one dam on the Volga River called the Volgograd Dam, which eliminated approximately 60 to 80% of the sturgeon breeding grounds in the area when it was constructed between 1958 and 1961.

The species is now highly reliant on adequate flows released from the reservoir above the dam, which are not always consistent, according to the agency.

All sturgeon, characterized by their long narrow body that can have armored plates, reproduce slowly, and many species require decades to reach maturity. Sturgeon do not spawn every year, and males and females often have different spawning and migration cycles, making reproduction even less certain.