by Jack Keller

My mom and I were sitting on our front porch enjoying a late September Sunday in our coastal Connecticut town of Rowayton. We were delighted by the abundance of bird songs. Robins, jays, cardinals, chickadees—the usual suspects—were coming and going, but Mom was fixated on another, a silent bird, on the neighbor’s roof.

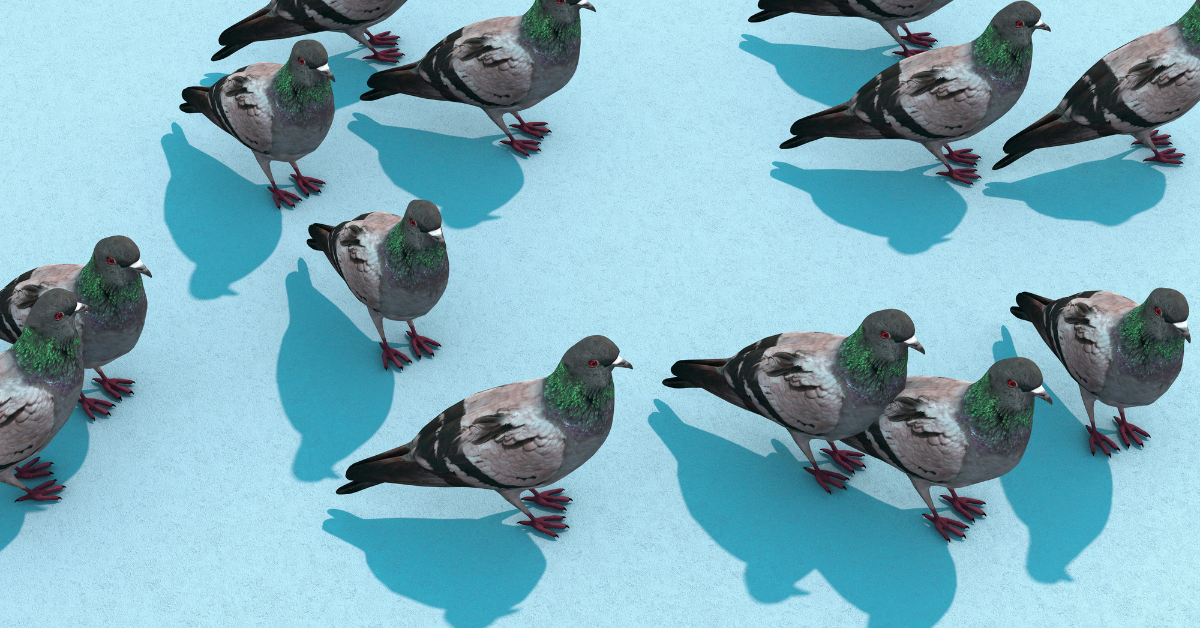

“What kind of bird is that?” She remarked as her eyes widened in marvel. I glanced up to find four beautiful pigeons, their iridescent necks shimmering in the late afternoon’s golden hues. They were leaning all the way back and carefully scaling and strutting their way down the treacherous roof like an adept hiker—they’ve done this before. They were pursuing a pool of water in the roof’s gutter and gawked their necks in triumph when they reached it. It’s clear that these ostentatious birds prefer the shingling to the natural canopies that their avian counterparts were occupying.

“Those are pigeons, mom.” I finally told her.

“Pigeons? Ew!”

Mom’s sudden shift in perspective got me to thinking. Why is it that some are only capable of appreciating the pigeon when they don’t know the bird’s identity? I’m certain others would act the same way mom did. Pigeon’s have been, after all, coined by a New York City parks commissioner as “rats with wings,” vermin in need of extinction.

My earliest memories of pigeons come from visiting New York and witnessing them feeding on trash and defecating on Dad. I didn’t question their much-maligned status or appreciate how well they’ve adapted to city life.

Much like the human New Yorkers they thrive in a concrete ecosystem, unfazed by the lack of the components of the natural world. Sociologist Colin Jeromlack told Audubon.org: “More than most other urban animals, they prefer concrete and sidewalks and ledges over grass and shrubs…pigeons invade the space that we’ve designated for people.”

The birds have strutted the streets for hundreds of years, arriving in the 1600s with some of the earliest European colonists, according to the New York Public Library. They were brought over to be raised for food.

Because of their incredible homing talents, pigeons have been exploited by humans for a long time, and they’ve experienced their own Forest Gump-like front row seat to plenty historical events.

Genghis Khan used a system of pigeon relays from Asia to Europe to keep up to date on happenings across the empire. Romans would send pigeons between cities to announce Olympic Game winners. Sailors lost at sea would often release a pigeon to point them in the direction of land. They were used in World War I—and in plenty of other conflicts—to carry critical messages.

Their bright red eyes mark spectacular human-like vision. They can fly up to 500 miles in a day and have been recorded flying at speeds of 94 mph.

They’re also astonishingly intelligent. Pigeons can recognize themselves in a mirror, something only a select few nonhuman species are capable of. They’ve also been trained to discriminate between four-letter-words and four-letter combinations that are not words. They develop complex bonds and are monogamous birds who mate for life.

Friends of Animals is hoping a larger-than-life pigeon sculpture now installed on the High Line in New York City will help provide a different perspective on the pigeon rather than my mom’s “ew” factor. That was part of the intention of Colombian artist Iván Argote, the statue’s creator.

Tod Winston, an urban biodiversity specialist at NYC Bird Alliance, told MSN.com he finds a certain justice in the gigantic sculpture. “It’s like pigeon’s revenge,” he said, adding humans were fine to share their lives with pigeons when they were using them for food and carrying messages, but now that they’re feral, we don’t pay attention to them unless forced.

He pointed out that even the coloring and patterns pigeons display is remarkable. “If the rock pigeon were a rare bird, birders would be lining up around the block oohing and aahing over them because they’re really very beautiful,” Winston said.

We couldn’t agree more.